As some of you may know if you follow me on social media, I’ve been dealing with a minor shoulder injury. When I was around ten, I fell through a metal jungle gym, fractured my left wrist during the ten foot drop, and landed on my left side while at school. After going to the nurse and then having my parents take me to the ER, my wrist was treated and healed. But I didn’t realize until much later after I had became a more dedicated yoga practitioner that my shoulder had also experienced impact trauma and hadn’t healed properly, leading to over a decade of compensatory movement patterns. This is actually very common with impact trauma, as the instinctual reaction is to protect the area of the injury, often leading to postural habits that imbalance the body; for me, my instinct was to protect my left side even if I didn’t realize I was doing so.

Part of the lingering problem included an ability to slightly dislocate my shoulder, allowing my clasped arms to wrap around, up, and over my shoulders all the way to the back (yes, crazy I know). Yet for years, not understanding why I could do this and its connection to my lingering shoulder injury, I would dislocate my shoulders. It often felt like a great stretch through my upper back (even while I wasn’t learning to utilize my muscles to stretch the back). Admittedly, there was also some part of me that enjoyed the novel identity it brought, being able to do something so many people couldn’t do, especially considering I was never very athletic (book worm much?). Obviously, I have since stopped doing this.

As I have been going through my teacher training, I found that my practice was beginning to aggravate my shoulder. I’ve been practicing asana more than I ever have, and between the activity, weight bearing, long holds, and adjustments I’ve had to back off my asana practice for a bit and seek some medical and therapeutic help to let it heal properly, finally, after nearly twenty years. I am getting a variety of bodywork done to realign my left shoulder to proper placement, and am now trying to relearn proper postural habits to overcome over a decade of compensatory movement patterns. For me, this minor injury has actually been a profound learning experience in my own personal practice and has helped me think more deeply about my research, about what we are doing in asana, and about how we learn and think about yoga and the body in the Western yoga world.

Why do we think of yoga as only asana? In what ways have Western modalities of thinking influenced our understanding of the body as machine, and prevented us from a holistic connection and proprioceptive understanding of the body? What does it mean to have a deep yoga practice? How do certification programs reproduce and perpetuate limited views of yoga and the yoga body? And ultimately, how can we teach yoga as more than asana?

In sociology, we talk about how our ideas of health are socially constructed. What a healthy body looks like and the practices it engages in are socially determined through culture, socialization experiences, and medical practices. In the last century, western medicine has become a primary driver in our determination of “health,” often in ways that moralize the division between healthy/unhealthy, normal/pathological, pure/impure, such that marginalized populations are typically ascribed the status of “unhealthy.” In sociology, we call this approach healthism, and it is equally common in the yoga world where ideas of health, asana, and the body as machine mix in often dangerous and unanticipated ways.

Let’s look at an example of healthism in action. Women’s natural health systems, including pregnancy, menstruation, and menopause have been medicalized and pathologized for centuries. This is what I like to call (pseudo-)scientific sexism, and in the past included ideas that a woman’s uterus could travel through the body disrupting normal functioning (a “pathology” called female hysteria among Western psychology that wasn’t removed from their list of diseases until 1959), that a women who was menstruating was impure and dangerous, and (during the height of eugenics) that mental or physical exertion could actually damage future unborn children, an idea that was used to restrict access to higher education for women as it might “tax the brain” and damage our capacity for reproduction. And it’s important to note that these type of myths are not dead and gone! They survive in popular culture ideas that women are more emotional, that we experience PMS that interferes with our judgement (for which there is NO sound medical evidence), and misnomers like the popular “women shouldn’t lift weights” adage. In yoga, we often hear outdated ideas about not practicing certain poses while during our periods, despite the complete lack of scientific evidence as to why this might be necessary.

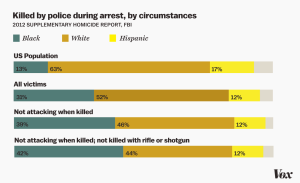

We could take this further to discuss (pseudo-)scientific racism, as well as popular ideas of size as a determinant of health that are similarly problematic and rooted in cultural and social myth rather than fact, but I think you get the idea. The point I’m trying to make here is that, especially in the Western world, we often like to think we understand what “health” means and how to practice it. But sociology teaches us that these ideas, like all knowledge, are socially constructed, historically situated, constantly changing, and can often lead to flawed understandings about the body, especially bodies of marginalized groups like women, people of color, larger bodies, queer bodies, and so on.

And if you are feeling reactive in light of this information, and want to proclaim, “Amara, how can you say that health is constructed? That PMS is a myth? WHAT?! *mind blown*,” know you are not alone. When I teach medicalization in my classes, my students often have similar reactions. This is because we are taught from infanthood to accept these ideas as absolute, indisputable “natural,” “truth.” It’s very uncomfortable to challenge something we have internalized and believed in for most of our lives. In fact, a great deal of social psychological research shows that people who are confronted with their own biases become defensive and reactive. But ultimately, confronting deeply ingrained misperceptions is the art and practice of yoga: to acknowledge the biases that we have internalized that drive our actions, and to overcome these illusions to get at a more accurate and pure understanding of our Selves and the world around us so that we can act from a place of knowledge and intention, with mindful awareness (which we can think of as a practice of vinyasa krama).

In yoga philosophy, we refer to the biases of the mind as maya, illusion, or avidya, incorrect comprehension or ignorance that clouds our perception, that is the “accumulated result of our many unconscious actions, the actions and ways of perceiving that we have been mechanically carrying out for years” (Desikachar’s Heart of Yoga). Such habitual bias colors the mind, obscuring our clarity of perception and preventing us from achieving true understanding of our Selves and world. The art of yoga is about overcoming this ignorance and illusion to foster a deeper understanding, so that we can avoid and alleviate suffering in our lives and others.

Healthism, Yoga, and the Body as Machine

During the past century our understandings and ideas about the body within yoga have been heavily influenced by Western medical practices and healthism. Historically, the incorporation of anatomy into yoga was driven by an interest in eugenics in the early 1900s (a topic thoroughly researched by Joseph Alter) and by the cross-cultural transmission by yoga gurus like B.K.S. Iyengar, who often utilized medical science to appeal to a Western audience and to legitimize yoga in the modern world. In this process of transformation yoga increasingly became defined as asana, which was more accessible and easier for Westerners to understand as it corresponded to already existing ideas of fitness practices and provided a tangible path of progress to follow. It was also easier to teach in group class settings than the more classical understanding of yoga as a philosophical practice.

What this meant is that yoga became synonymous with asana, disconnected from philosophical practices, and tied to medical science, particularly the use of anatomy, predicated on dividing the body into separate parts and systems rather than viewing the body as a holistic physical, emotive, and mental being. So we now take classes, solely teaching yoga as asana, that “focus” on specific parts of the body: a class to work your hamstrings, a class to open the hips, a class to work the core abdominal muscles, a class to work the butt muscles, and so on. We learn that this pose is good for this ailment, this muscle, this system. And in teacher training systems we teach the body as consisting of seemingly separate parts: poses that work the legs, poses that twist the spine, the separation of the muscular, skeletal, and nervous systems, a division between structural and functional movement patterns. We divide the body up into parts of a machine, that work together but are presented as separable. And “health” becomes constructed as purely physical and as something that we achieve by isolating and maximizing the utility of seemingly disparate parts of the physical body without a clear end point (something illustrated clearly by the creation of numerous sequences in the Ashtanga method beyond the primary series; there used to be just one until the practice was Westernized and the later series were added on to meet the demand and expectations of students).

This view of the body and of health in yoga is flawed; the body is not divisible, and all the parts of our body are interconnected. The organs are not separate from the muscular and skeletal systems, but are intimately tied together into a functioning whole. The muscular and skeletal systems are interconnected, and alive; habitual functional movement patterns can actually change our skeletal structures over time. We cannot isolate the core muscles from other parts of the body, or target particular body areas to work on in isolation and when we try to do so we disconnect from the sense of the body as whole, the body as holistic, the body as flesh and blood rather than the body as machine. We also potentially increase the risk of injury. Not to mention that the body is not simply physical but also a mental and emotive being. Emotional and mental states can change the physical body, which, for example, is at the heart of current research on the psychology of eating. In asana, ideally, every pose is a entire body practice, not just of the entire physical body, but also of the mental and emotive body.

And these aspects of the body are not separate from the world around us, either. We are not contained in an isolated bag of flesh; as Stacy Alaimo argues in Bodily Natures, the body is transcorporeal and interconnected to the world around us. What we put on the body, like body products, enters into us through the pores of our skin. The toxins we are exposed to become a part of us as we breathe, and the social, cultural, and institutional influences on our lives have a profound effect on the physical, emotive, and mental practices of the flesh. For example, research has shown that poverty affects our mental behaviors and attitudes, as well as the physical being as those who are poor are more likely to suffer from a variety of health concerns like obesity, mental illness, or toxic exposure. Gendered socialization can actually change the way the brain works. The body is ultimately permeable and porous, and as yoga philosophy teaches us all of these things are constantly in change, constantly in flux (even our bones).

This holistic, transcorporeal approach to health is gaining ground in Western science, and is being corroborated with recent biomechanical research on movement and stretching, on the new science of pain, on the psychology of eating and weight loss, on the existence of the microbiome, and in bodywork circles on the way emotional and physical trauma is held in the body across time. But most of the Western yoga world is woefully behind the times, as the regulations for teacher training systems have not been updated in decades and most certification programs primarily teach yoga as asana according to the body as machine approach to “health.”

In this “yoga as asana” approach, yoga becomes constructed as the achievement of various positions of the body, rather than a way or method of moving the body to prepare for the deeper, more meditative practice. Rather than think about how we practice asana, as a methodology of moving meditation and philosophical application practiced through the physical body, where the physical is joined with the emotive and mental and whose movement takes place in the world, we focus on disjointed poses or positions of the body and rarely pay attention to the transitions between postures. We focus on staying bounded on a mat, restricted in space, stuck in a box, rather than recognizing the movement in every moment, in every transition and position, as an extension and engagement with the world around us, wherever we are.

I like the term “chasing asana” to describe how we have become focused on chasing the sensation or achievement of individual postures, without a clear reflection or understanding (self-study, anyone?) of why and how we seek to attain these positions. What is the purpose of posture? In the Western yoga world, we teach students, and train teachers to teach, that the focus is on achieving the 2-d pose we see rather than feel, typically on social media and through popular culture (produced by the yoga industrial complex that profits often of this consumption-focus). And don’t be fooled! We are taught yoga is something to consume. To buy. To sell. To practice in small quantities in ritualistic and disparate spaces (studios), to keep on the mat, or to take asana off the mat, rather than as a way of living life throughout every moment, for a lifetime. And as a form of consumption, we can also think of this interpretation of yoga practice as a type of indulgence, because chasing asana is ultimately a practice of stroking the ego rather than non-attachment. Frustration that may come through injury demonstrates this, as we are attached to chasing asana, to yoga as asana, so that when we are unable to practice this interpretation of yoga we lose sight of the path, we lose sight of the practice entirely (although personally I haven’t been frustrated with my injury, I know many many yogis who have been with their own, and I have experienced this myself in the past when I was younger and did not understand yoga as deeply.)

We chase a construction of asana as individual positions, regardless of whether we have to force the body beyond its ability to get there, regardless of whether we are capable of muscular stability to prevent injury and ensure proper alignment. We don’t develop proprioception through deep self-reflection, mindfulness, and meditation on what we are doing, in every second, in every transition, as well as in every “end-point.” We are told to “listen to the body,” but never how to do so, or why. We are encouraged to “feel” but never taught how to interpret what we sense within the context of the lifetime, in the context of sustainability in our practice across time. We are encouraged to chase poses that biomechanically speaking often require us to go beyond a safe range of movement in the joints. We are encouraged to seek ego and pleasure through asana instead of practicing vairagya, non-attachment, in order to understand what is best for us and avoid being clouded by bias, illusion, avidya. We are encouraged to want to practice, rather than utilize practice to achieve what we need and encourage functionality.

We don’t teach asana within the context of yama and niyama, within the context of yoga philosophy. We don’t learn the classical purpose of asana as a means of learning to sense, understand, and master the body in conjunction with pranayama for the purpose of self-realization and elimination of suffering. Traditionally speaking, asana was one part of a larger practice of yama, niyama, pranayama and meditation, all of which allowed the yogi to, in a simplified sense, control the instinctual flight or fight response that leads to reactivity, instead developing a constant practice of acting with intentionality, knowledge, and purpose. The path of yoga is the path of learning how to act with intention through the development of self-realization, so that we may be a stable balance point in the sea of constant change, enabling us act from this anchor.

The construction of yoga as asana is exacerbated by the Westernized, militarized format of classes, which have changed from the individualized, one-on-one instruction between a student and teacher to drill-style group classes geared towards the average individual. This is based on the factory-style educational program that began after industrialization in the West which was also incorporated into the military, and subsequently spread to the rest of the world, including India.

In one-on-one instruction the teacher would create and gear lessons to the students’ individual needs and level of understanding. Lecture and discussion of philosophy and readings were common, and asana was taught according the individual student’s ability in conjunction with other yogic practices. But in the drill-style, group class setting there are time restrictions, we can’t assign homework or reading, there isn’t the degree of student-teacher contact, discussion of philosophy is limited to the brief moments of stillness in the midst of chasing asana. And even if teachers want to break free from this mold it can be extremely difficult, as many make a living teaching and in order to earn their income must meet the expectations of paying, student consumers who learn about yoga through popular culture and come to class with prior expectations of what they are paying for that put pressure on teachers to present yoga as only asana. While there are some ways around this, such as offering teacher trainings where trainers can teach yoga as more than asana (to a very limited degree), private classes, reading groups, and the like, these are more difficult to achieve and to find strong student support for.

So I’d like to leave this post with a few questions for myself and everyone out there to think deeply on. What is the purpose of asana, and why do we chase it? What are we really gaining by achieving more complex postures, or practicing 108 sun salutations (which, really, no one should do if they want to avoid repetitive stress injuries)? At what point do these practices become a practice of ego, and devoid of the deeper aspects of yoga? To what extent do we consume yoga, rather than practice or study it, because of industry expectations and encouragement? If the body is transcorporeal and holistic, rather than a machine, then how can we transform our asana practices to reflect this? How can we utilize asana as a tool to gain self-knowledge and self-realization, a tool to practice the deeper philosophy of yoga? (Because a tool is only as useful as how it is wielded; a hammer can just as easily injury you as build a roof to sleep under.) What are we teaching about the body and self if we are not reflecting on the bodily habits (physical, emotional, and mental) in our everyday lives, both on and off the mat? In what ways do we compensate physically, emotionally, and mentally in our practice, why do we do so, and how is this written in flesh?

Love, light, and… yoga ❤